Collecting and transporting ocular fluids

Ocular fluid biochemistry can help diagnose causes of sudden death. The eye is relatively isolated and protected so collection of ocular fluid up to 48 hours after death can add value in an investigation.

Testing can include:

- urea and nitrate/nitrite poisoning

- cyanide poisoning

- pregnancy toxaemia/ketosis (beta hydroxybutyrate)

- ruminal acidosis (D-lactate)

- hypocalcaemia

- hypomagnesaemia.

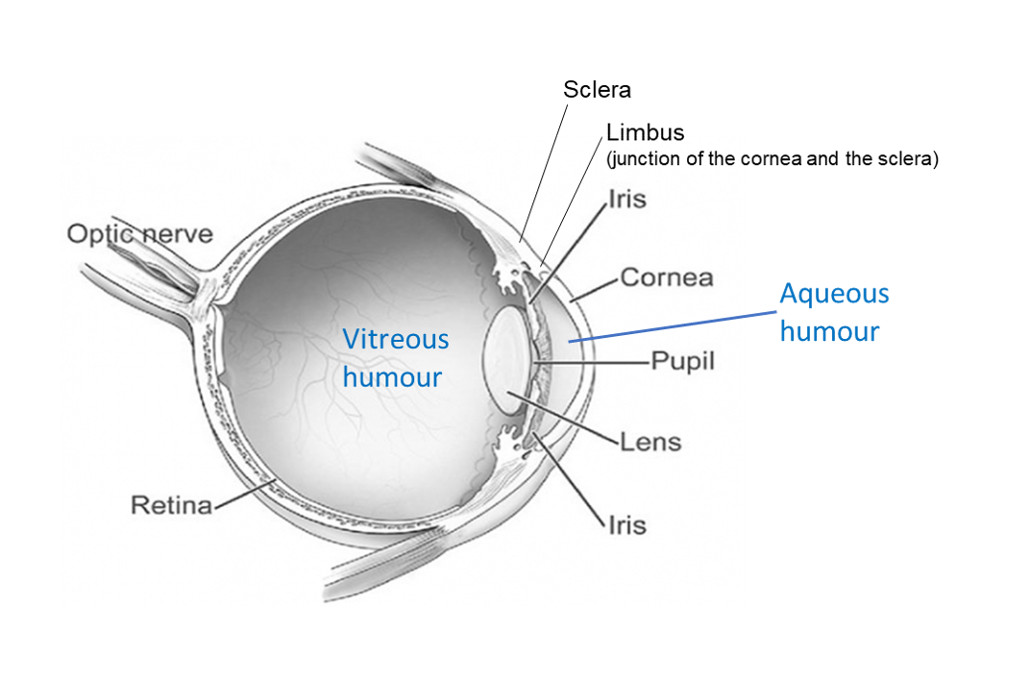

Photo by Edwards, Foster and Livesey 2009.

Steps to collect either aqueous or vitreous humour

- Use an 18-gauge needle and 3 mL syringe (rather than a vacutainer to reduce the likelihood of getting tissue contamination of the sample – which can affect results).

- Aqueous humour is the watery contents of the anterior chamber. Insert the needle horizontally just below the cornea. Face the bevel of the needle towards the cornea to avoid the iris.

- Vitreous humour is the gel-like contents of the posterior chamber. Insert the needle via the sclera into the centre of the globe behind the lens (the tip of the needle may be seen through the pupil). The needle and aspiration may need to be slightly adjusted to collect the viscous fluid.

- If there is blood contamination, start again on the other eye with a fresh needle and syringe.

- Transfer the samples to plain blood tubes (without anticoagulant) for transport. Choose as small a tube as you can to reduce the airspace above the sample (to avoid evaporation of analytes).

- Collect from multiple animals that fit the case definition.

- Most samples should be chilled (for ruminal acidosis, ketosis, hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia, salt poisoning, nitrate/nitrite). Immediately freeze sample for cyanide and ammonia testing. Alternatively, for cyanide testing, you can send the whole eyeball chilled.

- Label and send to the lab as soon as practicable.

- Results must be considered in relation to clinical history, gross pathology and the estimated time of death. Reference ranges are not available for many analytes, but extreme values are likely to be useful indicators of a particular disease or exposure to a toxin.